#2 in my Ranking of Alfred Hitchcock’s films.

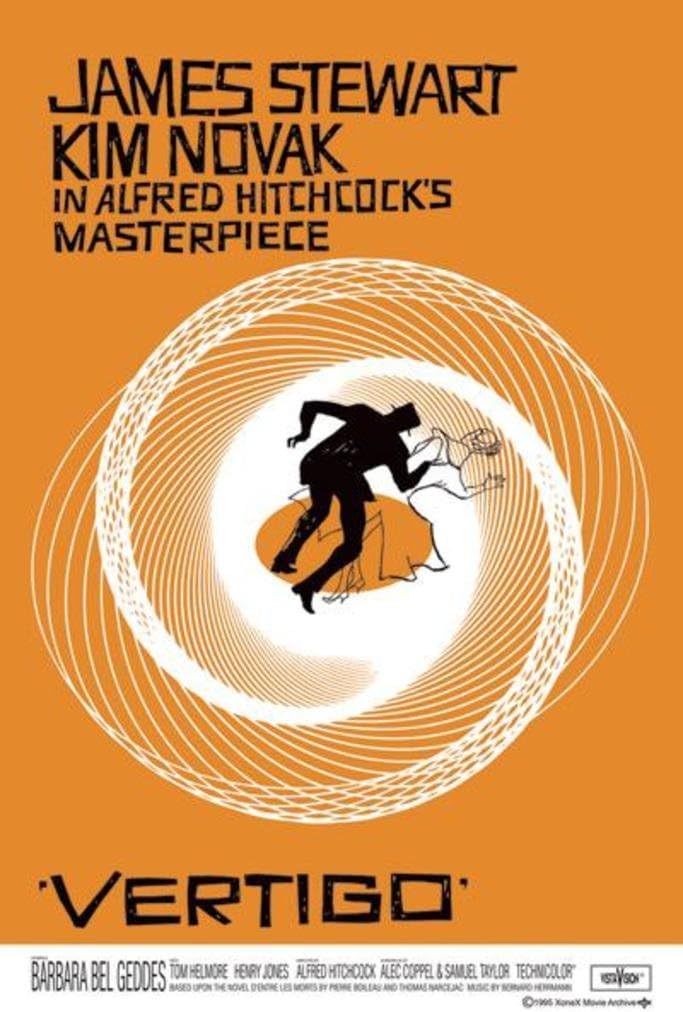

From the opening credits, it’s easy to tell that there’s something darker and weirder about this journey into obsession and control from Hitchcock. The music from Bernard Hermann is haunting. The neon spirals spinning against a black background are a visual representation of the trippy journey to come. And then we get a prologue where we watch our main character Scottie running along rooftops until he’s clinging for his life and another policeman falls to his death trying to help him. Thinking back over Hitchcock’s other movies of this vein (Notorious, Spellbound, and Rope in particular), credit sequences were lighter, opening scenes were less heavy and brighter (even in Rope, the murder happens quickly and then it begins to lighten up visually), and there were far fewer ominous tones bounding about. I don’t know what it was about the script based on the novel D’entre Les Morts that got Hitchcock to push his opening this far in a new direction, but I think it works fantastically at setting the scene.

Vertigo was in a series of films Hitchcock was making where he was trying to use his Hollywood cache to expand what kinds of films he could make. From the cinema verité aesthetics and narrative of The Wrong Man back to the one-shot technique of Rope, Hitchcock was trying to move beyond the term Hitchcockian and make movies that simply interested him. Vertigo, despite its reputation as his best movie (if you believe the Sight & Sound poll) and his most emblematic, it actually feels like it’s missing a few of the basic elements that make a movie Hitchcockian. There’s no wrong man. There’s no chase. It’s not a breakneck thriller like The 39 Steps or North by Northwest. There’s no real MacGuffin. It’s a dramatic mystery, more in line with Rebecca than almost anything else he made.

There are definitely other common elements at play, for sure. The blonde Madeleine fits in rather well with his other blondes, though she’s a deeper, more sympathetic character than most. There’s voyeurism both explicit and implicit (Madeleine got naked into Scottie’s bed somehow). It’s not out there completely in terms of what made Hitchcock movies Hitchcockian, but it does seem a step removed.

Anyway, I love it. It’s such a great film with a pair of main characters that both get incredibly sympathetic treatments. Scottie is a former policeman with a fear of heights that leads to vertigo who gets hired by an old college chum, Gavin, to follow his wife, Madeleine, who acts as though she’s possessed by the spirit of a low born woman raised to elegance and then discarded by a powerful Californian a hundred years before. What makes this plot interesting, I think, is that Scottie never falls into the belief of the possession. Up until the moment he loses Madeleine, he’s trying to appeal to her reason and past experiences in her own life, not the life of a long dead woman. What ends up making the romance work between Scottie and Madeleine is that Madeleine isn’t a real woman, but an ideal created by Gavin to appeal to Scottie. On the other end, the woman playing Madeleine, Judy, ends up falling for Scottie because of something she says later, that she’s been pursued by many men, heard many lines, and implies that she’s only had bad experiences with men. Scottie, who comes to her genuinely and wanting to help her without taking advantage of her is something she’s never experienced before.

The tragedy of the film is that the two would never have come together if it hadn’t been for Gavin’s plot to kill his own wife, but that same plot is what separates them in the end. When Scottie finds Judy, he can’t help but fall in love with what Judy could be rather than who she is. The plot continues to be destructive long after it’s ended because Scottie can’t let go of the woman who never existed even as the actual woman he fell in love with stands in front of him, hoping against hope that he’ll see her instead of the fantasy, but because she loves him, she lets him transform her back into the fantasy. The hurt that Scottie feels at having been lied to is deep, but so is the hurt that Judy feels for receiving nothing back from the man she loves for who she is herself. She knows she’s little more than an object to him, but she can’t let it go.

There’s a dream sequence late in the film that recalls, to a certain extent, the dream sequence in Spellbound, but the effectiveness of the two is a marked contrast. In Spellbound, the basic actions of what we’re seeing get explained in voiceover along with an explanation. In Vertigo, it comes at Scottie’s low point, presents its series of images, and never gets mentioned again. It’s a cinematic demonstration of Scottie’s emotional state at that point, and the unnatural way the images are put together, along with the haunting score by Hermann, heighten the moment for the audience. The former was interesting visually but used poorly while the latter is both great to look at and serves a strong purpose in the story.

Now, reading up a bit on the film, I discovered that there was one particular editing fight that broke out between Hitchcock, his regular editor George Tomasini, and the studio where Tomasini and the studio wanted to keep in a scene late in the film where Judy writes a letter to Scottie admitting her involvement in the plot that she never sends. Hitchcock wanted it cut, but he lost the argument and kept it in. Having read that before I rewatched the film, the scene stood out a bit and I began thinking of what the movie would be without it, and I think it would have worked better. We can see Judy’s emotional troubles with becoming another woman for Scottie, but I don’t think we need the explicit reveal that early. The final reveal with the necklace and the admission at the church tower in the final moments of the film would act as confirmation of what the audience had begun to suspect, helping to build the mystery without, I think, detracting from Judy’s emotional fragility and depth.

There’s an extra push in this film emotionally and artistically that sets it atop most of Hitchcock’s filmography. In particular, it’s his best looking film. The colors are so deep and vibrant, especially the restaurant Eddie’s with its deep red walls contrasting with the dull grey of Scottie’s suit and the pop of green from Madeleine’s scarf. The hotel room where Judy finally fully becomes Madeleine is the stand out, though. The green of the exterior sign of the hotel is Madeleine’s color (she wears green the first time we see her, her car is green, etc.) and as Judy walks out of the bathroom fully transformed, she’s bathed in a green glow that has a literal explanation and a metaphorical one (the manifestation of a fantasy). The use of color is so precise in Vertigo and so wonderful to look at, that it’s such a sumptuous visual treat to simply look at.

I still prefer Notorious by a smidge, but Vertigo is a great film. It’s great to look at, it’s emotionally involving, and the mystery ends up playing second fiddle to the emotional arcs of the characters on multiple viewings. The movie actually gets better on rewatches because the characters are so well built that while Scottie is going through his end of the mystery that we already know, he’s not just following breadcrumbs. He’s building an ideal that carries him through the film to the end. Vertigo really is one of Hitchcock’s best films.

Rating: 4/4

Odd that there are no reader comments here, but whatever…I watched the 4K version of this and it’s magnificent and heart-breaking, but it was obvious that it was going to be a box office flop. Movie stars in the late 50’s were expected to be types (John Wayne, the stolid hero, Cary Grant the smooth lothario with a heart of gold, Elizabeth Taylor the imperious slut, etc) and Jimmy Stewart was the everyman nice guy. Except here.

Here, he’s really a creep, and an unsettling one. Granted, the inquiry scene, where Hank Jones basically roasts Jimmy, is a very good way of justifying his obsession, but it really doesn’t cover the fact that he got a young girl killed because of his psychosis. You know who would have been great? Anthony Perkins.

Anyway, it’s beautiful in image and sound and yes, one of the masterpieces of cinema. But there’s a number of reasons why people don’t put this in their binge-watch lists, unlike Hitchcock’s more heroic films.

LikeLike